Wappingers School District - Makerspaces Build STEAM for Learning

The Wappingers School District has taken an approach to STEAM education that supports and coordinates a variety of initiatives among its schools. Its efforts have contributed to learning that builds creativity, collaboration and communication skills across its K-12 educational community. In the process, it allows for deeper connections between disciplines, and organizing learning around principles that provide a powerful way to motivate and engage students. This article describes the story of how grassroots efforts across the district are leading to a synergy in support of STEAM education. It chronicles the development of makerspaces and highlights their impact on the school community.

As school districts across New York State devote resources to the integration of Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts, and Mathematics (STEAM), they are motivated not only by an understanding that these efforts will help prepare students for a changing economy, but also by the opportunities they can provide for teaching and learning. STEAM education engages students in an integrative approach across curricula and grade levels. It is taking shape in various ways, while simultaneously opening opportunities for re-thinking and re-designing classroom instruction and other learning opportunities within schools. It also aids in building “democratized” environments where students are guided rather than directed in their learning (Halverson and Sheridan, 2014)

The Wappingers School District is located in southwestern Dutchess County NY, about 75 miles north of NYC. With approximately 11,500 students enrolled K-12, it operates three high schools, two middle schools and ten elementary schools. It has taken an approach to STEAM education that supports and coordinates a variety of initiatives among its schools. Its efforts have contributed to learning that builds creativity, collaboration and communication skills across its K-12 educational community. In the process, it helps make deeper connections between disciplines, and organizing learning around principles that provide a powerful way to motivate and engage students.

A specific area of focus that supports STEAM education has been the creation of makerspaces. This process is closely tied to the district’s strategic planning efforts which have developed a culture of supporting technology integration initiatives within its schools. Although activities such as Lego League and Robotics exist in some of its schools, more recent developments at its middle and elementary schools have sparked interest in establishing makerspaces throughout the district. Experiences in these schools have shed light on how STEAM education generally – and makerspaces in particular – can have a positive impact on the climate and culture of a school.

Vassar Road Elementary School First Graders Tinker and Create

STEAM education can be done in many ways with many different ages of students. In Andrew Nikola’s first grade classroom at Vassar Road Elementary School, students utilize Lego building blocks to learn about communities and economics. They build places like parks, grocery stores and schools, then use a journaling app called SeeSaw to record a video of themselves explaining how what they have created is part of a community. They also use that app to label the parts of what they have created. Mr. Nikola believes that students can integrate their learning by designing and creating with the Legos. Nikola says, “they work with mathematics concepts before being formally introduced to those concepts in a lesson.” They are learning concepts such as the relationship between parts and whole by building with the Legos. Mr. Nikola does not direct activity; instead, he works alongside his students as they consult with him about their designs. He “asks them open-ended questions while introducing opportunities for productive failure and iteration.” Educators at the Children’s museum of Pittsburgh see this approach as an integral part of conducting “making” activities with students (Brahms and Wardrip, 2016). Mr. Nikola has built his makerspace by obtaining grants from organizations like Donor’s Choose. Most recently, he won a competitive grant from The New York State Computers and Technologies in Education (NYSCATE) organization.

Powerful things are happening when Mr. Nikola’s students can conceptualize something, build it, and then write about it in their journals, explaining what it is that they have built, and how it relates to community. Along the way, they are also learning to work together, by helping each other work out design problems. When it’s time for students to transition to a new activity, Mr. Nikola ends by displaying each journal entry to the class and asking students to share their ideas with the entire group. The makerspace provides valuable developmental communications skills applied in a context that is meaningful to them.

Not Your Traditional School Library

Building a habitat for a pet guinea pig is not an activity that one would expect for a library. But that’s what library media specialist Meredith Inkeles is currently doing at Kinry Road Elementary School. Her students decided that the library needed a pet, so each afternoon this month they have come to work in her library to create guinea, and build a habitat. But this pet won’t need to be fed, nor will its cage need to be cleaned, because it has been created entirely out of Legos. This is just the latest among many projects that Ms. Inkeles has been integrating into her library since she decided to turn it into a makerspace. After attending a makerspace summer camp, she decided to establish one in her school library media center. She believes that, “students need to have the freedom to engage in low-stress types of learning challenges, and a makerspace can provide that in a fun and safe way.”

Ms. Inkeles has also added an “R” to what she calls STREAM education. Not surprisingly, she sees the “R” as standing for reading. During challenges, such as one which uses stop motion animation, she shares books on the topic with her students. Like many of her colleagues she has acquired new resources and opened her library to new learning activities. Each afternoon, during the last period of the regular day, she welcomes groups of students to the makerspace where they can explore any of the resources independently or participate in one of the challenges that she has set up. Students at Kinry Road Elementary School are welcoming this new use of their library. By having time to tinker, they are free to comfortably explore what interests them and develop the motivation to make connections to the traditional curriculum.

The Van Wyck Junior High Innovation Center

The Van Wyck Junior High School discovered what can happen when teachers and students are challenged to explore, create, and share their talents. In the spring of 2015, ELA teacher Christine Furnia proposed an idea to convert a former computer lab at Van Wyck Junior High School into a genius bar where students would help each other use technology. Establishing a space where students were encouraged to explore their interest in working with technology was a natural extension of what they were doing in her class. The principal at Van Wyck, Dr. Steven Shuchat, was receptive to the idea and offered support for the establishment of a room where students could explore their interests in using technology.

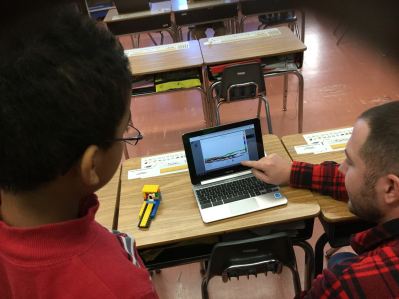

As the new school year began in the fall of 2015, the Van Wyck Innovation Room opened with only a few computers and minimal resources. In an important show of support for the initiative, the room was staffed with teaching assistant Theresa Maher who would be responsible for overseeing activities and supporting students. Some members of the faculty offered to have their supervisory duty in the room. A committee was formed to establish guidelines for its use, including procedures for how students would access the room. Work was done with the teaching assistant and faculty members involved to learn about similar initiatives in other schools, and an understanding soon emerged that the room was evolving into a makerspace. The teaching assistant was encouraged to learn more about what happens in a makerspace and one of the faculty committee members enrolled in an online course about makerspaces.

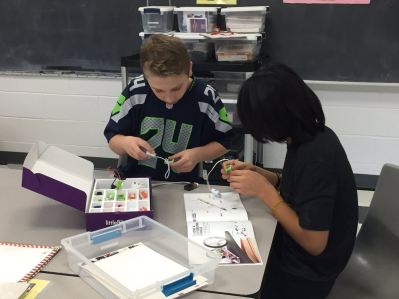

As winter set in, the Van Wyck Innovation Room was becoming a popular place students visited frequently during study periods and lunch. Students were periodically presented with “challenges” which required them to think, design and create. Since its inception, students have engaged in a range of activities such as, engineering challenges, collaborative artwork, designing the room, learning to use the 3D printer, creating public service announcements with a green screen, and celebrating the school’s 50th anniversary.

As activity in the Van Wyck Innovation Center increased, the educators involved in guiding its growth began to see some extraordinary things happening. An educational milieu was developing that included distinctly diverse groups of students coexisting in a common space. Regular opportunities arose for students to interact with one another, while engaging in the process of collaborating, sharing and learning. On one occasion, I observed a special education student explaining how he designed a series of circuits for the heating and lighting of a project that involved building a model urban community. Another student from a self-contained class worked side-by side with students on their lunch period, sharing knowledge about how to use Tinkercad to design an object for the 3D printer. A teacher who has her supervisory duty there remarked, “there are no labels in this room.” The Van Wyck Innovation Center functions as a community space where all present enjoy opportunities to learn together. Moreover, its atmosphere affects those looking to explore new ideas and integrate new ways of learning in much the same way an auditorium stage invites musicians and artists to perform.

Special education teacher, Joseph Glauda, volunteered to do his supervisory duty in the Innovation Center because he was supportive of an initiative that would provide students with new learning opportunities. After spending time with students in the Center, he became interested in learning more about makerspaces. That led him to enroll in a graduate course where he learned of the Happy City Project, described by Honer and Kanter in their book, Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators. Looking for a more meaningful way to teach geometry, he decided to have his students use the Innovation Center to design a model city out of cardboard and other materials, based on ideas presented in the book. They were challenged to create and explain physical representations of the geometry that they were learning, while also providing opportunities to apply multi-disciplinary skills. It grew to include heating and lighting systems, and even bilingual street signs. To extend the project, Mr. Glauda applied for and received a grant to build scale model solar installations as part of the model. And this year, a committee of educators from Van Wyck has designed a new project to build a scale model of the local village of Hopewell Junction. There are even plans to integrate the use of the Center’s 3D printer for designing and creating components of the project. The learning experienced by Joe and his students from the Happy City Project provides powerful evidence of why the “Z axis” matters. By engaging in authentic work his students were able to move from 2D geometric representations to building 3D objects and thus engage in deeper thinking and ultimately express their understanding of the relationship between mathematics and the physical environment.

These and other projects in the Innovation Center embrace Papert’s constructionist approach to learning. Adults in the Innovation Center understand that their primary role is to facilitate growth by allowing students to “self-organize” their learning. They understand the value of “reaching across the divide between formal and informal learning,” to create a common place where a focus on the “who, what and how of learning without getting hung up on the constraints that govern different settings” (Halverson and Sheridan, 2014). Joe’s experience illustrates how the presence of a makerspace can encourage an environment of immersive professional learning (Childs and Crichton, 2014).

One of the remarkable things about the existence of a makerspace like the Van Wyck Innovation Center is the influence it can have on improving the practice of the educators in the school community. Professional development frequently takes place when teachers who visit the Center find themselves in the role of learner, receiving support from a student or colleague. When teachers and students co-exist as learners in the Innovation Center, opportunities for learning together can easily present themselves (Stager, 2017). Educators at Van Wyck have begun to see the Innovation Center as place where they can initiate new learning opportunities for their students and for their own professional growth.

Supporting the Creation of Makerspaces District-wide

Each of these initiatives has helped educators, students and parents in the Wappingers Central School District understand how developing a makerspace brings exciting opportunities to teaching and learning. They illuminate an approach to personal learning that is both interdisciplinary and exploratory. As a result, there is a greater understanding of why STEAM education can motivate both students and educators to be more engaged in their work. In an important show of support, the Wappingers Central School District Board of Education earmarked funds to renovate rooms adjacent to the libraries in its secondary schools. All four buildings now have rooms that are designed as collaborative working and learning spaces with specialized furniture, whiteboards, and enhanced display capabilities. The progress continues, as the district is currently re-aligning its elementary libraries, calling them Learning Centers in support of STEAM education.

As the tide of interest promoting STEAM education continues to rise in Wappingers Central School District, a greater understanding about its integration is developing among educators. They increasingly are understanding the value of creating an environment where students are provided with extended opportunities to explore areas of interest, in “communities of practice” and where they are free to associate and collaborate with others, beyond the constraints of the traditional curriculum (Sheridan et al., 2014). By creating a makerspace in his classroom, Andrew Nikola’s first graders are building critical “self- organization” skills while simultaneously learning the basics of mathematics literacy. Ms. Inkeles has become an advocate for STREAM education by transforming her library into a dedicated makerspace each day. At Van Wyck Junior High School educators know how STEAM related efforts can motivate students to express their understanding of design principles through transdisciplinary learning (Keane and Keane, 2016). Joe Glauda’s experience with the The Happy City Project and all that is happening at the Van Wyck Innovation Center is evidence of how designating a makerspace where students and adults can choose to meet and learn together to “invest in their own inventions,” can produce remarkable benefits for the school community (Martinez and Stager, 2013). What all these initiatives have in common is an acknowledgement that there is a need for students to have a place at school where expectations for what is to be learned come primarily from themselves. Efforts to build makerspaces are leading educators in the Wappingers Central School District to engage in new thinking about what motivates children to learn, and how that can profoundly impact their own practice.

References

Brahms, L., & Wardrip, P. S. (2016). Making with young learners: An introduction. Teach Young Children, 9(5), 6-8.

Owens. Crichton, S. s., & Childs, E. e. (2016). Taking (2014). Learning in the Making: Making into Schools Through Immersive A Comparative Case Study of Three Professional Learning. Proceedings of The Makerspaces. Harvard Educational Review: European Conference On E-Learning, 144-150. December 2014, Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 505-531.

Honey, M., & Kanter, D. (2013). Design, Libow Martinez, S., Stager, G.S. (2013). Invent make, play: Growing the next generation of to Learn: Makers in the Classroom. Education STEM innovators. New York, NY: Routledge. Digest, 79(4), 11-15.

Keane, L., & Keane, M. (2016). STEAM by Papert, S. (1993). The Children’s Machine. Design. Design & Technology Education. Technology Review, 9628-36. 21(1), pp. 61-82. Stager, Gary (2017). Unconventional Wisdom.

Kimberly Sheridan, Erica Rosenfeld About The Maker Movement. District Halverson, Breanne Litts, Lisa Brahms, Administrator Special Report, pp. 6-10. Lynette Jacobs-Priebe, and Trevor.

Resources

- Starting a School Makerspace from Scratch

- 6 Strategies for Funding a Makerspace

- Maker Education

- Maker Ed

- Renovated Learning

- Makezine

- The MIT Makerspace

- Donors Choose

- NYSCATE

- Invent to Learn: Making, Tinkering and Engineering in the Classroom

Contact

Paul Rubeo, Technology Integration Specialist in the Wappingers School District, adjunct faculty in the School of Education at SUNY New Paltz, paul.rubeo@wcsdny.org